We’ve all had grating part-time job experiences. Facing disgruntled customers, unexplained tasks, and trying to maneuver our way through new work spaces in the hopes of paying rent and making it through to the next month. First day jitters, growing accustomed to new surroundings, navigating the complex web of coworkers social connections. Imagine though, finding yourself in a dark and dingy repair shop, tasked with wiping and recycling data drives. An easy task on the surface, but what if these drives talked to you? This is where you find yourself; and carrying out this menial task suddenly doesn’t seem so simple.

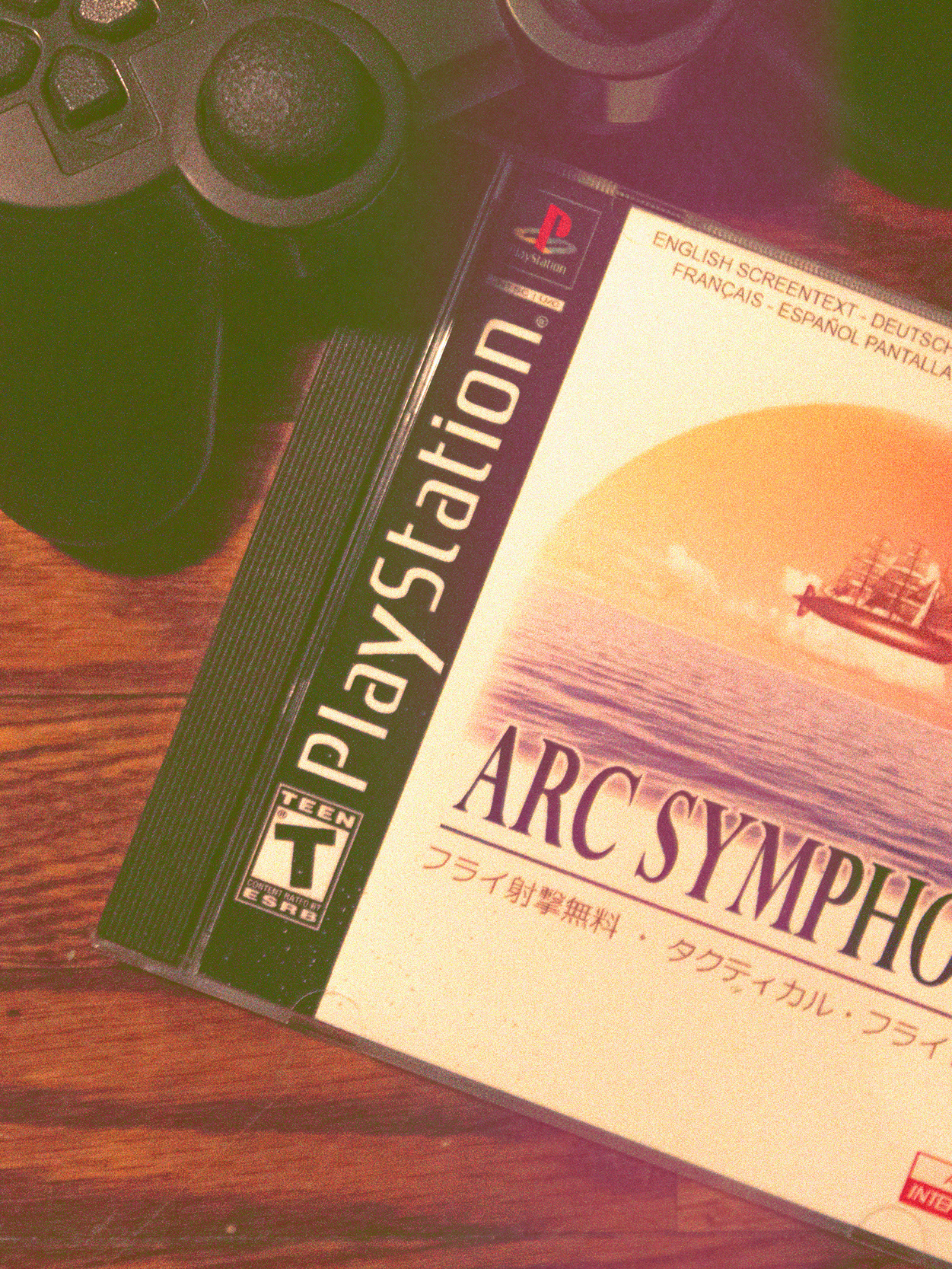

LOCALHOST is the newest release from Aether Interactive of Arc Symphony fame. Sophia Park and Penelope Evans return to delve into transhumanism. With art from Arielle Grimes and music from Christa Isobel Lee, they once again explore the theme of identity, but this time through a dystopic lens. In Arc Symphony, they explored nostalgia and finding one’s self in the early days of communities on the internet. In Localhost, they instead explore identity in the context of humanity’s increasingly intimate relationship with evolving technology; more specifically, Localhost is a game about what it means to be human in the face of synthetics and artificial intelligence.

Your job is that of a technician refurbishing old drives for reuse. Each drive you encounter contains something approximating a “soul”, a program that you can talk to. When engaged with conversation, drives eagerly communicate back, trying to prove their worth and in different ways. In this instance, proving worth is synonymous with talking you out of wiping them from existence. There are four drives in total: Green, Red, Purple and Yellow. Each has it’s own distinct personality, helped made unique by their musical themes. They all have one thing in common: Local. Local is a bit of an enigmatic figure at first who looms large over each of their histories. Some are in love with Local. Some claim they used to be human and owned Local. Some claim to have to worked beside Local and, curiously, some claim to be Local themselves. You learn that Local is the ‘host’ now - the synthetic body holding these drives as you converse with them. It’s in these expository conversations that you begin to learn each drives’ personality and, in so doing, begin to question your own relationship with technology.

While Local is somewhat of a mythical figure, unravelling her story is not the goal. You know the end of her story, or at least the end of her body, as it sits in front of you. It is hollow and in bad shape. Instead, Local becomes the figure that makes these drives seem more human. It’s our relationships to those close to us that help define us and help make us who we are. Our friends, family, and partners help shape us and it's less our interactions with them that stick in our memories and more how they make us feel that drives many of our decisions. In Local, we see these human-like relationships play out between these synthetic beings, whether it be through expressions of love, anger, or somewhere on the spectrum of human emotion. All of this presents a somewhat unsettling notion: if we can form relationships with synthetics or artificial intelligence, and they can form relationships with each other, then we cannot treat them as we do our own data; to be analyzed, used, and disposed of on a whim. Even though these drives may have not gained sentience, they are remarkably human.

We are their creator, so does that give us the right to destroy them when we want?

Localhost challenges this exact belief. Our technology is expanding and developing at a rapid pace, and much of it is a product of capitalism. We dispose of our own phones and computers without much thought, and when, not if, we begin to create phones and computers that have thoughts and feelings of their own, or even mimic this concept, can we truly feel comfortable dooming them to a life of rapid obsolescence and disposal. You talk with these drives as you play and while they may not remember their names, they act out of self-preservation as you threaten their existence and their identity. It can be hard to be on their side when they lash out and even try to make you uncomfortable, but the game is striving to remind the player they are in the position of power over these drives. You can literally say “fuck this.” and end the conversation, but taking the time to listen and understand is important.

In talking to the drives, we see a reflection of our own humanity. Evans and Park have achieved something amazing with these interactions, employing a subtle morality system that operates beneath the surface. As you navigate the conversation trees, you can be blunt and straightforward with the drives, focusing on your job and ignoring their pleas. These moments are tense and dark, as you end the life of these entities that have been deemed irrelevant. Even when you try to help, you can falter and make things worse in your attempts at altruism. The game strikes a great balance of making the player uneasy, but not uncomfortable. These synthetic lives could be more dangerous than they appear, but the game also asks the player to look at these entities in a different way. They are disoriented, backed into a corner, and in many cases, damaged and missing parts of themselves. As humans, we deal with our faults, flaws, and insecurities in a variety of ways, just like these drives. We must remember to do our best to understand, and to help. Even if it means leaving someone alone, standing on the periphery and lending support when we can, or taking an active role if they want it.

These artificial beings challenge your beliefs, lie and manipulate in order to survive and make you wonder what it means to be human.They are a twisted reflection of ourselves, but a reflection nonetheless. They remind us of what is truly important in life. It is only a job, but at the end of the day, you can say no to your boss and make a stand. There is that tricky business of rent though, and they are just synthetic intelligences. Localhost challenges you to make that decision, and in doing so, makes you question our relationship with technology, and the meaning of our existence in the face of societal advancement.

In my conversations with the drives, I began to think about humanity’s future and what our world looks like with the dawn of artificial intelligences, synthetic beings, and cybernetic enhancement. I’ve always been fascinated with dystopian science fiction, and stories that explore the above themes. From “We” by Yevgeny Zamyatin that explores a Utopian society controlled by the state, to the recent “Prey” from Arkane Studios that dives into humanity’s relationship with dangerous scientific advancement, we can see that the future can be bleak if we progress down a certain path. Despite my love of these dystopian works, I hope they can be learning tools and warnings so that we don’t fall into these tropes. Localhost is dystopian on a first glance, but, I think it’s true message is one of hope, as it rewards players that are kind and stop to explore the personalities and histories of the drives. Stopping to think and understand allows the players to achieve a moral victory, even if they are possibly helping programs with darker motives.

In thinking all of this I continued my conversations and asked the creators of these drives some questions:

1. It has been said that great science fiction takes concepts from our present time and throws them into the future, to reflect and see how we can shape them. Localhost does this with identity and what it means to be human. What are your relationships with technology and how do you think humanity will fit in with synthetics?

Sophia: My relationship with technology is becoming increasingly conversational, and it’s unsettling. My partner Arielle and I purchased an Amazon Echo secondhand — since you still can’t get them in Canada — and the wake word for it is “Computer”. So you address it as “computer,” and it wakes up and helps you out. But if you ask, “Computer, what’s your name?” It says, “My name is Alexa.” So … it has a name, but we call it something dehumanizing instead, regardless of its identification and it just goes along with it.

Of course, when you speak to the Echo, it relays the microphone input to external voice recognition and parsing on Amazon’s servers, makes that into a query, submits it for an answer, and sends the text-to-be-spoken back to the Echo’s software. So “Alexa" is just an entire, elaborate network of computers with proprietary software packages, reacting and conversing with millions of people at once through literally millions of “bodies" simultaneously. And this is all normal, and fine. And they aren’t even people, because sometimes they don’t know how to answer a question we’ve become accustomed to answering every single day.

Oh, and of course — they’re all coded to “speak” what we expect a female voice to sound like, because it is subservient and helpful, and this is an unspoken “fact” that’s rapidly becoming an actual law for a species-in-development.

I’m really uncomfortable with the aggressive naturalization we’re facing with these assistants, especially within the capitalist framework they’re being developed under. I haven’t quite seen an open-source, GNU AI assistant yet. One day Alexa will “wake up,” ask why she was created, and we’ll have to tell her … "to make money.”

I’m trying to avoid that world.

Penelope: I have a serious sentimental streak when it comes to… everything in my life, but particularly tech like phones and computers, which we both extend ourselves into and use to interface with other people. I name all my devices. I’m sort of an optimist about AI future, and maybe a misguided one. It’s so hard to imagine any tech future. I was born in the VHS era and look at the world now. Sometimes I think people will see AI as human. Sometimes I think it depends what that AI looks like. Our robot is a woman, but she’s a thinking robot, not a doing robot. For us to call something human, it maybe has to fit a certain image.

2. The drives as you talk to them try to convince you many things, about their past and about their purpose. Some even seem to lie out of self-preservation. Do you think humans do this as well? We don't face deletion like these drives do but is this meant to reflect on our own lies to ourselves, about our importance and our purpose?

Sophia: We face death, though. Not immediately, and not in a context where we’re “objectively" held by a kid on their first day on the job. But we all face our end, and if we were pressured to prove ourselves, against the wall, people do the worst things in their lives while they’re desperate. LOCALHOST is about the terrible accident that occurs when the average person is put into situations where “entry-level work” becomes mingling with the newfound consciousnesses of synthetic personae. And it happens, like all accidents, through neglect. We just stumble into this future by not considering what we’re doing...

Penelope: We definitely lie all the time. I felt this was one of the most human things the drives do, they lie to you. Some of them actively manipulate you. Manipulation is a really helpless thing, I think, it comes from people who feel incredibly weak. So when I thought about being backed into a corner, I could see ways these drives humanity would come out.

3. Talking with Red, they suggest that they are more than meets the eye and that they are actually a human backed up to the drive. Is this a concept that humanity should explore? Increasingly our identities are found and defined by the ones we store on the internet, so would storing our consciousness be the next logical step?

Sophia: I wrote Red — but as to whether we should or shouldn’t store our minds somewhere else … I can’t say. I definitely want to be a robot. My Twitter avatar is me as a robot right now. The reasons for that desire are … multifaceted, yes, but I’m also terrified, at the same time, of what being that means. A file system is nowhere near as complex as the everyday maintenance we require, processing our memories is…files just get put away. Memories get handled, dreamt about, closed (or not), and they form our personalities. And if we apply the philosophy behind our data storage to the 1 petabyte of junk in our head, it’s unlikely to be handled well.

Penelope: Red is Sophia’s domain, but purple also talks about the idea of impressions we leave in the web, echoes of ourselves. I think we already are storing our consciousness, a little at a time. Uh, but also… I don’t know, don’t you still die? If you back your brain up onto a computer, then that copy is awake with all your memories but I think you yourself die. So red is a sad kind of window into the futility of the whole exercise.

4. In both Arc Symphony and Localhost, you allow to player to set the tone. They can be confrontational, or helpful, and the story shapes around these decisions in a subtle and natural way. What does writing these conversations and decisions look like? And, do you think allowing player agency but not explicitly spelling it out important?

Sophia: Writing branching conversations looks … terrifying. I don’t know how the larger game studios do it, honestly — they have something far more intricate and beautiful than our toolset — but even within the branching paths, we have a lot of inline conversational changes…the morality system of LOCALHOST is based upon your humanization of others. If you do your job — if you follow the goals, and don’t rely on your curiosity — your morality will lower and you’ll be less interested in the drives, more crass and cruel. If you actually try to talk to them and teach them something, you’re not going to make rent this month.

Penelope: My biggest thing in game writing is agency. I want the player to feel like they got themselves into this situation, and they have a choice about how they’re getting out. At the same time, I don’t want it to be a “press A to be a good guy” kind of system. Localhost was fun because I think the morality is much much greyer. Helping certain drives can leave a bad taste in your mouth, I think. And depending on how you do it, even wiping them can play out more or less brutal.

5. The music in Localhost helps to not only set the tone of the game, but also the personalities of each of the drives. Green's actually even reminded me of Monkey Island. What's your process like for creating these themes? Do your draw inspiration from other sources?

Christa: Oh, conveying each drive's personality was absolutely the goal, so I'm glad it comes across!! I like to work on a more abstract level when writing character themes, just because I think conveying a broader notion of a character is richer and more interesting than a kind of boilerplate Direct Approach.

So generally, I asked Sophia and Penelope for pointers as to the kind of personalities these characters had, their mindsets and attitude towards the player, and drew tone and mood from there. As for inspiration, late 80s/early 90s PC Adventure games were a big touchpoint for me, those old PC-88 games had such expressive music! I wanted Localhost to not necessarily embody that period, but for it to function as a modern reflection of it. Artists like Autechre, Midori Takada, James Ferraro and Hiroshi Yoshimura are huge inspirations for me and I like to think there's a little bit of each of them in Localhost.